Today we celebrate National Dentist Day. Suggestions for the day include delivering a thank-you note to your dentist—although I would recommend giving them the book of the day instead. For me, the greatest book ever written about a dentist is also one of the best picture books of the twentieth century: Doctor De Soto by William Steig.

In the stock market crash of 1929 Steig’s father lost everything, and, as a young man, Steig had to work to support his family. He could draw with great finesse and believed if he became a commercial artist he would have the best chance of putting food on the table. He sold his first cartoon to The New Yorker in 1930 and became their longest running contributor until his death in 2003, crafting scores of covers and more than seventeen hundred drawings.

Steig was a late bloomer when it came to children’s books and didn’t start publishing them until he was sixty. A fellow New Yorker artist, Robert Kraus, founded his own small publishing house, Windmill Books, and began enticing his friends to be authors and artists. With Windmill, Steig published Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, which won the Caldecott Medal in 1970. And with that he launched his next career, one that continued for thirty-five years.

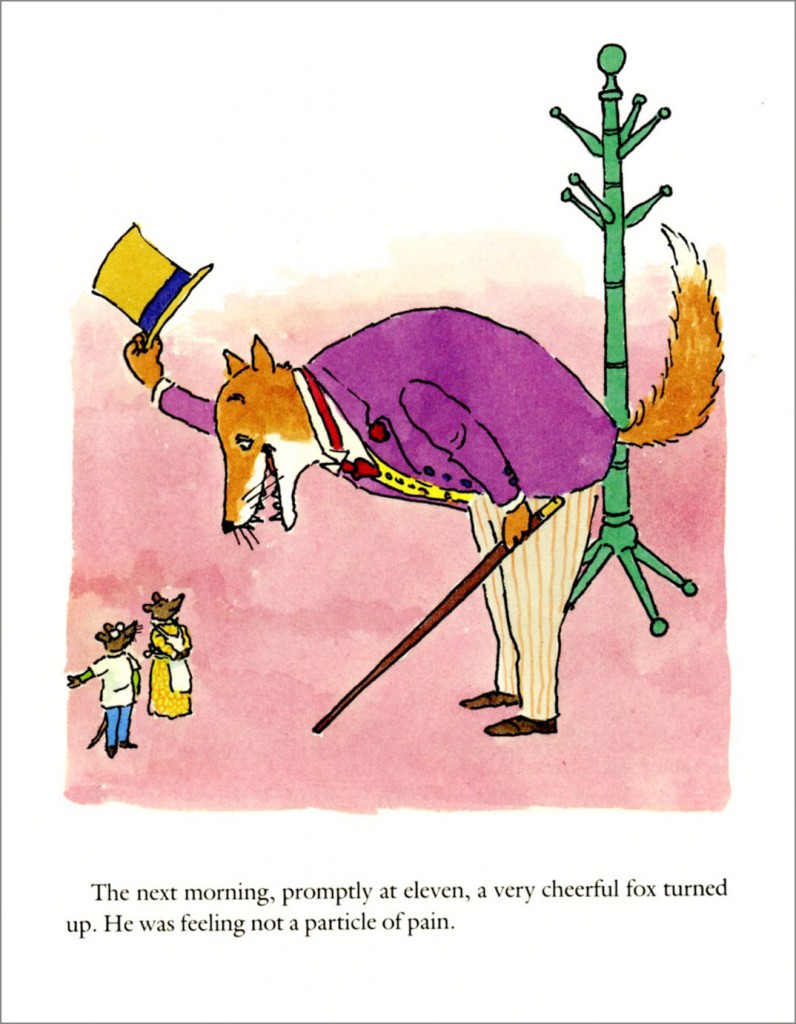

In Doctor De Soto, William Steig explores what would happen if a mouse dentist suddenly had to deal with a fox as a patient. White-smocked and of good cheer, Doctor De Soto treats his larger patients, such as cows and donkeys, by climbing onto a ladder and using a hoist to get into their mouths. No one is more dedicated than the good doctor, although he does refuse cat patients, for obvious reasons. When a fox with a rotten bicuspid shows up, Doctor De Soto uses all his own cunning—and a little help from modern science. Readers watch with glee as the protagonist and his wife outwit a wily fox.

Steig’s art always looks fresh and vibrant, but that spontaneity actually took a great deal of work to achieve. Using Picasso as his model, Steig worked from a loose pen line and began his drawings with a face or an expression. If readers look closely at Steig drawings, they see the drooping mouths, raised chins, or narrowed eyes that reveal what the characters are thinking and feeling. Steig’s language matches his artwork to perfection. He always chose the right phrase. The text of Doctor De Soto, in fact, won a rare honor for a picture book, a Newbery Honor Award. His characters—Brave Irene, Shrek, Amos and Boris—enchant children. His language, humor, and playfulness make the books totally satisfying for all ages.

I am very grateful for dentists on this day that honors them. But I must admit, I would go a good deal more cheerfully to the dentist office if I thought I’d find Doctor De Soto there to greet me.

Here’s a page from Doctor De Soto:

In the stock market crash of 1929 Steig’s father lost everything, and, as a young man, Steig had to work to support his family. He could draw with great finesse and believed if he became a commercial artist he would have the best chance of putting food on the table. He sold his first cartoon to The New Yorker in 1930 and became their longest running contributor until his death in 2003, crafting scores of covers and more than seventeen hundred drawings.

Steig was a late bloomer when it came to children’s books and didn’t start publishing them until he was sixty. A fellow New Yorker artist, Robert Kraus, founded his own small publishing house, Windmill Books, and began enticing his friends to be authors and artists. With Windmill, Steig published Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, which won the Caldecott Medal in 1970. And with that he launched his next career, one that continued for thirty-five years.

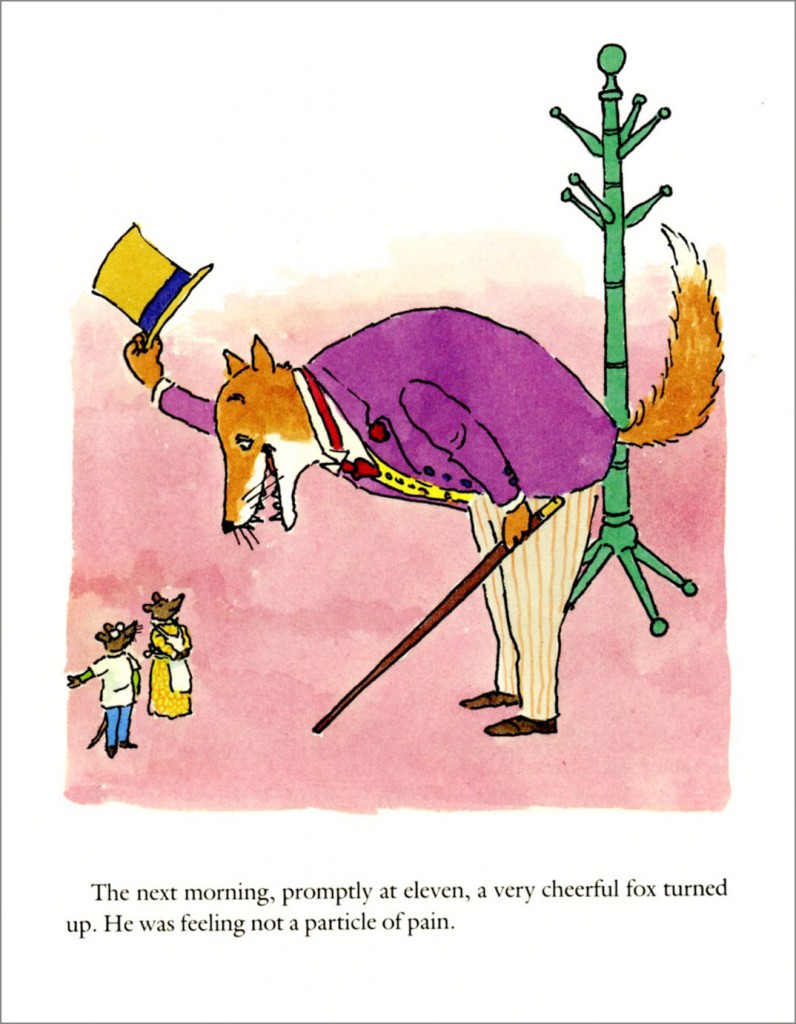

In Doctor De Soto, William Steig explores what would happen if a mouse dentist suddenly had to deal with a fox as a patient. White-smocked and of good cheer, Doctor De Soto treats his larger patients, such as cows and donkeys, by climbing onto a ladder and using a hoist to get into their mouths. No one is more dedicated than the good doctor, although he does refuse cat patients, for obvious reasons. When a fox with a rotten bicuspid shows up, Doctor De Soto uses all his own cunning—and a little help from modern science. Readers watch with glee as the protagonist and his wife outwit a wily fox.

Steig’s art always looks fresh and vibrant, but that spontaneity actually took a great deal of work to achieve. Using Picasso as his model, Steig worked from a loose pen line and began his drawings with a face or an expression. If readers look closely at Steig drawings, they see the drooping mouths, raised chins, or narrowed eyes that reveal what the characters are thinking and feeling. Steig’s language matches his artwork to perfection. He always chose the right phrase. The text of Doctor De Soto, in fact, won a rare honor for a picture book, a Newbery Honor Award. His characters—Brave Irene, Shrek, Amos and Boris—enchant children. His language, humor, and playfulness make the books totally satisfying for all ages.

I am very grateful for dentists on this day that honors them. But I must admit, I would go a good deal more cheerfully to the dentist office if I thought I’d find Doctor De Soto there to greet me.

Here’s a page from Doctor De Soto:

Also recommended: Mr. Dentist by Anne Rockwell

Originally posted March 6, 2011. Updated for 2012.

No comments:

Post a Comment