Illustrated by Robert Lawson

On July 18, 1936, General Francisco Franco led an uprising of army troops in North Africa against the elected government of Spain. So began the Spanish Civil War, sometimes called “the first media war” because foreign correspondents and writers became involved—people like Ernest Hemingway and George Orwell. One would not expect this event to have much effect, at all, on American children’s books. By and large, children’s book publishing in the United States tends to be myopic, focusing inward rather than on world events.

However, timing is everything—in publishing, then and now. And the Spanish Civil War looms large as the defining publicity event for one of our classic picture books, The Story of Ferdinand. This seventy-page saga, illustrated with black-and-white drawings, began as something of a lark. Munro Leaf felt that bunnies and kittens had been done to death in picture books, and he wanted a more memorable protagonist—so he chose a bull. Robert Lawson, who also lived in New York City at the time, delighted in incorporating visual puns and references into his art. For this Depression Era book, their publisher Viking printed around 1,500 copies. But everyone involved in this creation had some pretty shocking surprises in store.

Because of the Spanish Civil War, people began to look for political messages in this story about a Spanish bull. Some thought it was Fascist, some Socialist, and some Communist. It was banned in Spain and in Germany as degenerate propaganda. But many opinion makers—including Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt, Thomas Mann, H. G. Wells—rose to the book’s defense. When it comes to children’s books, any censorship attempt always sells a lot of books. As a society, we simply don’t want anyone telling us what our children should or should not read. The next year, eighty thousand copies were sold, and The Story of Ferdinand became a staple on the bestseller list.

Censorship can get books started, but not keep books going. What has sustained The Story of Ferdinand over the years is the wonderful interplay between the Leaf’s text and Robert Lawson’s art. The book does have a message—but not one about the Spanish Civil War. Pete Wentz of the rock group Fall Out Boys recently wrote about The Story of Ferdinand: “The book provides an amazing metaphor for how people can be. There’s something really honorable about following your own path and not doing what’s expected of you. When we recorded ‘From Under the Cork Tree,’ we experimented with different sounds. …When we are ninety years old and on our deathbeds, it will matter to us that at least we took chances and followed our own path.”

Seventy-five years after Munroe Leaf wrote The Story of Ferdinand, young readers still respond to its gentle humor, its advocacy of taking one’s own direction, and its happy ending. Just as Leaf and Lawson believed, the book tells the story of a bull that, in the end, was very happy.

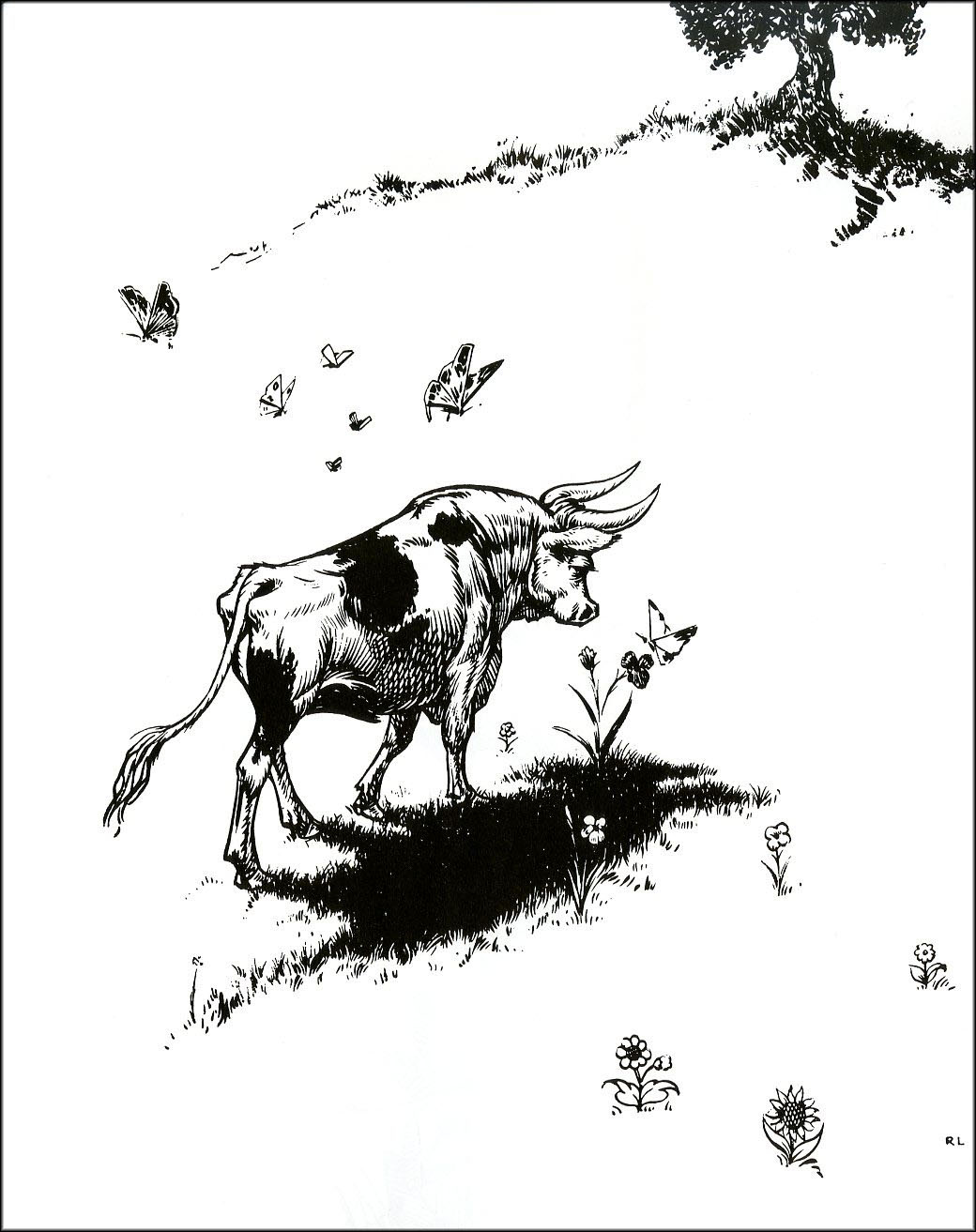

Here’s a page from The Story of Ferdinand:

All the other bulls ran around snorting and butting, leaping and jumping so the men would think that they were very very strong and fierce and pick them.

Ferdinand knew that they wouldn’t pick him and he didn’t care. So he went out to his favorite cork tree to sit down.

Also recommended: Wee Gillis by Munro Leaf, illustrated by Robert Lawson

Originally posted July 18, 2011.

No comments:

Post a Comment